Sample Research Paper: American Foreign Policy and the North Korean Nuclear War Crisis

This 3,891-word sample of our “Political Science” research paper writing expertise contains Harvard style citations, a list of data, diagrams, and scholarly references.

Research Paper 13 pages (3,891 words) Sources: 11 Style: Harvard Topic: Government & Politics

North Korea Research Paper Introduction

In light of the 2017 nuclear missile crisis between the United States and North Korea, we decided to write this example research paper to provide our visitors with some historical background information regarding the complicated, tense relationship between the two countries.

In light of the 2017 nuclear missile crisis between the United States and North Korea, we decided to write this example research paper to provide our visitors with some historical background information regarding the complicated, tense relationship between the two countries.

One of the strangest and most volatile places on earth today is the so-called “Hermit Kingdom” of North Korea. In fact a state of war continues to officially exist between this country and the United States, and policymakers have become increasingly concerned about the nation’s intentions since it has acquired nuclear weapons and engaged in a series of missile tests that could deliver them. To date, American foreign policy can be best viewed as a stalemate, and little progress has been made in compelling North Korea to abide by mandates from the international community concerning its abysmal human rights policies. American foreign policies for North Korea are clearly not working, then, but it remains unclear what approach might be best suited to help bring this Cold War holdout to the bargaining table in substantive ways. To help shed some light on the underlying issues and the mysterious leaders that have ruled the country since the end of World War II, this paper provides a review of the related literature to develop a background and overview of North Korea, what foreign policy decisions have worked and which have not, and an analysis of current and future trends. A summary of the research and salient findings are presented in the conclusion.

Research Paper Review and Discussion of US / North Korea Foreign Policy

An analysis of foreign policy as it relates to North Korea quickly assumes some unwieldy dimensions, with the cast of characters involved being nebulous and ever-changing, with a heady sense of paranoia overriding everything about the country. As Nau emphasizes, “No subject in the world is as complex as foreign affairs. You are dealing not just with natural facts, such as disasters and disease, but also with social facts such as human beings who change their minds and behave creatively. Natural facts–like a virus–don’t do that. They behave according to fixed laws” (p. 25). When it comes to North Korea, though, an analysis of foreign affairs is not only complex, it can be downright baffling. In fact, for a peninsula whose historic appellation has been “Land of the Morning Calm,” the historic events that have wracked both Koreas over the years have been anything but calm. According to Scobell (2007), “Winston Churchill once remarked that a certain country was “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” Of course, the statesman was referring to the late great Soviet Union, but this could also be said of present day North Korea” (p. 117). Indeed, when North Korea is mentioned today, it is usually in the context of its mysterious leadership and it looming potential nuclear threat that has South Korea and Japan jittery, and the cease-fire that dates to the end of the Korean War just does not seem all that reassuring anymore. According to Hagstrom and Soderberg (2006), “The centrality of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, North Korea) to politics in Northeast Asia has been underscored above all by the country’s suspected development of nuclear weapons since the early 1990s” (p. 373).

Like other historic crossroads of humanity, the Korean Peninsula has been the site of countless battles over territory among the various actors in Northeast Asia over the centuries. In this regard, Hagstrom and Soderberg note that, “This is the geographical spot where the interests of China, Japan, Russia and the US have overlapped and occasionally collided, often with dire consequences for the sovereignty of the Korean people” (2006, p. 373). In fact, the past two centuries have witnessed the Korean peninsula thrust into a series of violent upheavals, caught in the middle of wars between external powers with the adverse impact being particularly pronounced in the North. For instance, the struggle for suzerainty over Korea resulted in the Sino-Japanese War that took place from 1894 to 1895, and even though Korea was declared independent based on the defeat of the Chinese, the truth of the matter is competition for control continued to wrack the country (Hagstrom and Soderberg 2006). Just a decade later, for example, the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) took place and military forces from Japan shocked the world by defeating the old great power. In addition, the Portsmouth Peace Treaty recognized Japan’s “paramount interest” in Korea; however, it was not until 1910 that Korea was formally annexed by Japan and remained under Japanese colonialism for the next three and a half decades (Hagstrom and Soderberg, 2006, p. 373). Resentment against the Japanese for their harsh treatment of the Korean populace runs high on both sides of the 38th parallel, and reparations for the treatment of North Korean citizens in particular remains a high-profile issue among the North Korean leadership today.

Following Japan’s defeat in World War II in 1945, the country lost all of its former colonial possessions, including both Koreas. At the time, Japanese soldiers who were stationed north of the 38th parallel in Korea surrendered to the Soviet Union forces, and those who were stationed south of it capitulated to the military forces of the United States (Hagstrom and Soderberg 2006). At the time, the Korean people on both sides of the dividing line were of a like mind in wanting to pursue a path to freedom and independence that had been so elusive for them over the centuries. Nevertheless, the United States and other allied powers were determined to keep the military forces where they might be needed and the decision was made to administer the country for a period of 5 years. According to Hagstrom and Soderberg, “Since they could not agree on how to appoint an independent Korean government, the peninsula remained divided–a division that was cemented through the proclamation of the Republic of Korea (ROK or South Korea) and the DPRK in the fall of 1948” (2006, p. 374). The division of the peninsula, though, did little to qualm the political divisiveness that became increasingly apparent following the end of World War II, and the ground was being laid for the turmoil that would follow. In this regard Hagstrom and Soderberg emphasize that, “Both governments laid claim to the whole peninsula, and tensions between them became aggravated and ignited the Korean War in 1950. American-led forces fought on the ROK side, while Chinese and Soviet forces supported the DPRK. Fighting continued until 1953, when an armistice agreement was reached” (Hagstrom and Soderberg 2006, p. 374)

As noted above, as a result of the colonial legacy, anti-Japanese feelings remained strong in both Koreas and for some time there was no direct Japanese involvement in either country. Due to its central position within US policy for Northeast Asia, however, Japan became indirectly involved, and during the Korean War many US-led troops left for the battlefield from Japan. During the Cold War, the course of Korean affairs remained heavily affected by the antagonism between the US, Japan and South Korea on the one hand, and the Soviet Union, China and North Korea on the other (Hagstrom and Soderberg 2006, p. 374). Clearly, just as throughout the centuries, the Korean peninsula remains surrounded by divided interests that have affected the manner in which foreign policies initiatives have been formulated in recent years, but some important changes took place during the closing decades of the 20th century that continue to have a major impact today.

In the early 1970s, a climate of detente brought about the establishment of relations between China and the US and the normalization of relations between China and Japan. At this time, there was also some improvement in Japan-North Korea relations. From the mid-1970s bilateral relations deteriorated again, and they grew even worse as a result of the North Korean bomb attack in Burma in 1983, directed against the South Korean cabinet. In retaliation to sanctions imposed by Japan, the North Korean government detained and imprisoned two crew members from the Japanese fishing vessel Fujisanmaru, which had been captured in North Korean waters (Hagstrom and Soderberg 2006, p. 375).

Other hard facts about North Korea, though, are difficult to come by and even more problematic to confirm, but U.S. government analysts have developed some current insights about the country. What is known is that the North Koreans maintain one of the largest military forces in the world, an exceptional allocation of scarce resources for a country its size and in its economic straights. In this regard, U.S. analysts report that North Korea remains one of the world’s most centrally directed and least open economies, and is wracked by chronic economic problems (North Korea 2009). Weather-related problems, especially recurrent droughts, continue to adversely affect the country’s ability to feed its people and much of its industrial infrastructure is antiquated and is some of it has passed the stage of being repaired as a result of decades’ of neglect by the North Korean government due in large part to a lack of resources for this purpose. Beyond these fundamental constraints, there are other indications that the regime is in major trouble, including a discernible decline in industrial and energy production over the past decade (North Korea 2009).

Analysts with the U.S. government report that because of severe summer flooding followed by dry weather conditions in the fall of 2006, the nation experienced its 13th year of food shortages because of on-going systemic problems including a lack of arable land, collective farming practices, and persistent shortages of tractors and fuel (North Korea 2009). Energy shortages in particular are apparent from satellite images of the Korean peninsula at night that clearly show a brightly lit South Korea while north of the 38th parallel, everything is almost completely dark. During the summer of 2007, severe flooding again occurred. Large-scale international food aid deliveries have allowed the people of North Korea to escape widespread starvation since famine threatened in 1995, but the population continues to suffer from prolonged malnutrition and poor living conditions. Large-scale military spending draws off resources needed for investment and civilian consumption (North Korea). Despite its laudable but given its paucity of resources somewhat misguided policy of “juche” (self-reliance), the North Koreans do not possess the natural resources, technology or wherewithal to go it alone in an increasingly globalized marketplace.

In 2002, U.S. President George W. Bush proclaimed North Korea as part of the infamous “axis of evil,” a designation that has since served to irk the North Korea leadership to no end and which may have played a role in the decision to pursue nuclear research in defiance of international agreements to the contrary. Nevertheless, there were some minor encouraging signs that also took place in 2002, when the North Korean government codified a framework in which private farmers’ markets have been permitted to sell a broader range of goods; in addition, the government also allowed some private farming on an experimental basis in an attempt to increase agricultural production (North Korea 2009). Typically, though, the government of North Korea has once again reversed itself and by October 2005, these reform policies had been outlawed and the private sale of grains is no longer allowed; the government has also reinstalled a centralized food rationing system (North Korea 2009).

By December 2005, the government cancelled almost all humanitarian assistance operations from the international community throughout North Korea, preferring to receive developmental assistance only; at that time, the country’s leadership also restricted the activities of the international and non-governmental aid organizations that remained in North Korea, such as the World Food Program (North Korea 2009). According to U.S. government analysts, currently, external food donations are from China and South Korea primarily (North Korea 2009). In addition, at the time, South Korea also agreed to develop some of North Korea’s infrastructure and natural resources and light industry during a summit meeting that took place in October 2007. Nevertheless, North Korea remains tightly bound in the grip of a totalitarian regime and there are no signs that indicate anything is going to change for the better anytime soon (North Korea 2009).

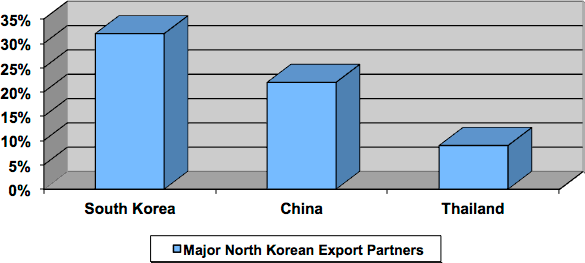

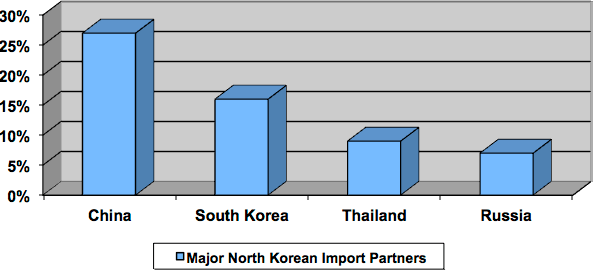

As can be seen in Figures 1 and 2 below, South Korea, Japan and China in particular have much at stake when it comes to their foreign policy dealings with North Korea. According to Scobell (2004), “The predominant tendency has been for Beijing to keep a low profile and adhere to ‘maximin principle,’ whereby China seeks to maximize the benefits of a policy initiative, while at the same time minimizing the costs it expends” (p. 21). In fact, China may well regard North Korea – in spite of its wacky and dangerous leadership – as a useful buffer zone between the U.S.-influenced South Korea and its own borders so that it can continue to pursue its economic development without interference from this potential hotspot. In this regard, Scobell adds that, “Beijing’s current foreign policy priority is to maintain peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific, and its domestic priority is to ensure continued economic growth and prosperity in China” (2004, p. 21).

Figure 1: Major North Korean Export Partners

Source: Based on data in CIA World Factbook (2009)

Figure 2: Major North Korean Import Partners

Source: Based on data in CIA World Factbook (2009)

Over the years, literally hundreds of thousands of North Koreans have become sufficiently desperate with the conditions in their country to try to escape over the border into China, but the Chinese government regards the North Koreans not as refugees in need of salvation, but rather as illegal aliens (Hilsum 2007). According to this analyst, “China will not allow the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) access to the border area, and limits the number of South Korean diplomats in the region, for fear they will encourage North Koreans to seek asylum” (Hilsum 2007, p. 36). As a result, this weird and secretive Orwellian state has been the focus of an increasing amount of attention from foreign policy analysts in the United States and abroad who are seeking to identify some crack in the regime that can be exploited to the West’s advantage, but the North Korean state keeps a tight lid on its activities as well as its citizens. In this regard, Martin (2003) advises that, “George Orwell’s 1984 is no mere literary fantasy. If you were North Korean, Big Brother would watch you. Pyongyang’s internal spies and thought police are everywhere” (p. 265). Indeed, if the situation was not so desperately dire and did not involve actual humans, what has passed for governmental operations in North Korea could be considered downright wacky and comical. Some interesting observations in this regard concerning North Korea are provided by Hilsum:

- Healthcare and education are provided according to government assessment of an individual’s and family’s political loyalty.

- Usually only children of the elite are allowed to go to college and hold prominent jobs.

- Between 1996 and 2005 more than $2 billion of food aid was delivered to North Korea.

- Approximately 37% of young children are clinically malnourished.

- Approximately one-third of mothers are malnourished and anemic.

- A citizen can be sentenced, without judicial process, to a life of “hard labor” in mining, timber-cutting, or farming.

- In 2003, the government announced that it would finally refrain from executing criminals in public.

- In 2004, a government campaign called on men to keep their hair short, stressing the “negative effects” of long hair on “human intelligence development” (2007, p. 37).

When North Korea tested a nuclear weapon in late 2006, it became abundantly apparent that the United States’ diplomatic approach to containing North Korea’s military ambitions was failing. In this regard, Lankov (2007) reports that current U.S. foreign policy is founded on the assumption that pressuring the small and isolated state will force it to change course; however, this has never occurred in the past and this analyst suggests that it never will (Lankov 2007). According to Lankov, “North Korea’s Kim Jong II and his senior leaders understand that political or economic reforms will probably lead to the collapse of their regime. They face a challenge that their peers in China and Vietnam never did–a prosperous and free ‘other half’ of the same nation” (2007, p. 71). Given the events of closing decades of the 20th century, it is little wonder that North Korea’s leadership is worried about the tenability of their own continuing control of the country. In this regard, Lankov adds that, “North Korea’s rulers believe that if they introduce reforms, their people will do what the East Germans did more than 15 years ago” (2007, p. 71). Taken together, there are a number of reasons that the North Korean leadership may want to continue this bizarre ritual of brinksmanship by vexing the United States, South Korea and Japan while walking a very fine line with its primary benefactor, China.

As a direct result of these diplomatic shenanigans, the North Korean political leadership’s perspective of the international scenario provides them with a number of valid reasons – at least from their view – to continue the status quo and keep the international community guessing and nervous about the country’s future intentions. Indeed, by continuing the policy of brinksmanship, North Korea’s leadership is able to exact what amounts of tribute from the international community in general and the United States and its allies in particular just to keep things from snowballing out of control on the Korean peninsula. In this regard, Lankov emphasizes that, “If anything, foreign pressure (particularly from Americans) fits very well into what Pyongyang wants to propagate–the image of a brave nation standing up to a hostile world dominated by the United States” (2007, p. 70). Confounding the problem for all concerned, though, are the diametrically opposed goals for the Korean peninsula that China and the United States perceive are in their respective best interests. As Lankov concludes, “Sadly, the burden of encouraging change in North Korea remains the United States’ alone. China and Russia, though not happy about a nuclear North Korea, are primarily concerned with reducing U.S. influence in East Asia. China is sending considerable aid to Pyongyang” (2007, p. 70).

In the years that have passed since the first North Korean nuclear crisis, the fundamental propensity of Japanese foreign policy concerning North Korea has been to reinforce its transition from a position of ersatz engagement to that of an effort to contain the unwieldy regimen as evidenced by a number of unilateral sanctions that Japan has enacted in recent years. In this regard, Hughes advises, “Japan’s government has been increasingly pushed towards a position of containment, which it is difficult to back out of, or for pressure from the international system to overcome” (2006, p. 455). On the one hand, in his analysis of U.S. foreign policy concerning North Korea, Nau (2007) cites four facts that are related to North Korea’s development of nuclear weapons: (a) the accumulation of weapons-grade plutonium prior to 1994, (b) the 1994 agreement which froze the plutonium production program, (c) the start-up in the late 1990s of a separate uranium enrichment program, and (d) the termination of the 1994 agreement in 2002. On yet the one hand, though, from the perspective of analysts who suggest that direct negotiations with North Korea represents a superior foreign policy approach typically try to emphasize the foregoing second and fourth facts. In this regard, Nau notes that, “The freeze agreement prevented further production of plutonium and thus capped the amount of weapons-grade materials available to produce nuclear weapons. The termination of the agreement allowed North Korea to resume plutonium production and test a bomb in October 2005” (2007, p. 25). From this point of view, the cancellation of the agreement is regarded as erroneous despite the fact that North Korea has been determined to have started another uranium enrichment initiatives since its original project remained far from being able to produce the weapons-grade materials required for nuclear explosions (Nau 2007, p. 25).

From still another point of view, diplomats who are of the opinion that the best approach to foreign policy negotiations with the North Korean elite is to continue current sanctions and attempt to isolate the regime from the rest of the world tend to stress the foregoing first and third facts. As Nau points out, “North Korea already had weapons-grade material before 1994 and could have tested a bomb at any time with that material. Moreover, it broke the 1994 agreement by starting up the enriched uranium program” (2007, p. 25). As a result, canceling the 1994 accords failed to accomplish anything of substance beyond making it clear what was transpiring in the secretive North Korean regime anyway, which Nau states was a covert program intended to acquire nuclear weapons. According to this analyst, “Better from this point of view to rally allies and isolate North Korea until it disclosed and dismantled all nuclear weapons programs” (Nau 2007, p. 26). Despite the many reversals that have been experienced over the years, some analysts believe that things are changing – at least a little – and these changes are the crack in the regime that they have been awaiting. For instance, Lankov emphasizes that, “North Korea has changed, and its changes should be boldly exploited. The communist countries of the 20th century were not conquered. Their collapse came from within, as their citizens finally realized the failures of the system that had been foisted on them” (2007, p. 71). In order to capitalize on these changes, though, Richardson (2007) suggests that a fundamental sea change in foreign policy thinking is needed on the part of U.S. policymakers. In this regard, Richardson notes that, “In dealing with other states, the United States needs to stop considering diplomatic engagement with others as a reward for good behavior. The Bush administration’s reluctance to engage obnoxious regimes diplomatically has only encouraged and strengthened their most paranoid and hard-line tendencies” (p. 26). While these observations were made with Middle Eastern countries such as Iran in mind, Richardson adds that, “The futility of this policy is most tragically obvious with regard to North Korea, who responded to Washington’s snubs and threats with intensification of their nuclear programs” (p. 26). Adding fuel to North Korea’s political fires has been the U.S. administration’s characterization of the country as a member of the notorious “axis of evil,” and North Korea remains solidly on the Department of State’s lists of state sponsors of terrorism. According to Peed (2005), “Most observers believe that countries like North Korea, which the State Department acknowledges is not known to have sponsored any terrorist acts since 1987, remain on the list primarily as bargaining chips for the end-game of nuclear negotiations” (p. 1321).

North Korea Research Paper Conclusion

The North Korean leadership continues to rattle its sabers, but now they are nuclear-tipped. It is little wonder that the divided Korean peninsula continues to be the focus of worldwide concern and because no official armistice has ever been signed by the belligerents involved, it would be a fairly straightforward matter for the fourth largest army in the world to aim its guns at Seoul and march across the 38th parallel once again. The outcome of such a renewed conflict, though, would be less certain than the previous engagement, and it could well be that the North Koreans could succeed at conquering their southern neighbor, at least in the short term. “The Dear Leader” may be ailing, but he still appears to possess the wherewithal to prosecute a fighting war with South Korea and its staunch but overextended ally, the United States.

Research Paper References (re: North Korea)

Hagstrom, Linus and Marie Soderberg. 2006. “Taking Japan-North Korea Relations Seriously: Rationale and Background.” Pacific Affairs 79(3): 373-374.

Hilsum, Lindsey. 2007, February 26. “North Korea: Survival Means Slavery Many North Koreans Are So Desperate to Escape the Country That They Are Prepared to Risk Their Lives. For Women the Choice Is Stark: To Die of Hunger or Be Sold as Brides in China. Lindsey Hilsum Reports.” New Statesman 136(4833): 36-37.

Hughes, Christopher W. 2006. “The Political Economy of Japanese Sanctions towards North Korea: Domestic Coalitions and International Systemic Pressures.” Pacific Affairs 79(3): 455-456.

Lankov, Andrei. 2007, March-April. “Bringing Freedom to North Korea.” Foreign Policy 159: 70-71.

Martin, Bradley K. 2003. Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Nau, Henry R. 2007. “Why We Fight over Foreign Policy.” Policy Review 142: 25-26.

North Korea. 2009. U.S. Government: CIA World Factbook. [Online]. Available: https:// www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/kn.html.

Peed, Matthew J. 2005. “Blacklisting as Foreign Policy: The Politics and Law of Listing Terror States.” Duke Law Journal 54(5): 1321-1322.

Richardson, Bill. 2007. “A New Realism: Crafting a US Foreign Policy for a New Century.” Harvard International Review 29(2): 26-27.

Scobell, Andrew. 2004. China and North Korea: From Comrades-In-Arms to Allies at Arm’s Length. Carlisle Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute.

—. “Notional North Korea.” Parameters 37(1): 117-118.

Bibliography Tool: How to Reference This Paper in Different Citation Styles

“Sample Research Paper: American Foreign Policy and the North Korean Nuclear War Crisis.” A1-Termpaper.Com, 2018, https://www.a1-termpaper.com/samples/american-foreign-policy-north-korea/. Accessed 25 Apr 2024.

If you don't see the paper you need, we can write it for you!

Established in 1995

900,000 Orders Completed

100% Guaranteed Work

Simple Ordering Process

300 Words Per Page

100% Private and Secure

We can write a new, 100% unique paper!

Search Papers - Wed, Apr 24, 2024

Navigation

Home | Order | FAQ

Samples | Contact Us

Share With Friends