Sample Term Paper: Should Marijuana be Legalized in the United States?

This 2,900-word sample of our “Social Issues” term paper writing expertise contains Chicago style citations, a table, a diagram, an image, and footnotes (highlighted and hyperlinked for your convenience).

Term Paper 10 pages (2,900 words) Sources: 9 Style: Chicago Topic: Drugs & Alcohol

Marijuana Legalization Term Paper Introduction

One of the most notorious, failed social experiments of the 20th century was Prohibition, which transformed tens of millions of ordinary American citizens into criminals by virtue of outlawing the consumption of alcohol. Prohibition also created a new criminal class that was inextricably involved in the manufacture and distribution of this formerly legal substance. By the time Prohibition was repealed, an informed observer might suggest that the United States had learned its lesson the hard way and would not make the same mistake again. Alas, the same thing is taking place in America today, wherein tens of millions of ordinary citizens are deemed criminals because they enjoy smoking marijuana (herbal cannabis), and many are imprisoned as a result. This paper analyzes relevant peer-reviewed and scholarly literature to identify the controlling factors involved in the current legislation against marijuana, and what some states and other countries have done in recent years in an effort to decriminalize its use. A summary of the research and important findings are presented in the conclusion.

One of the most notorious, failed social experiments of the 20th century was Prohibition, which transformed tens of millions of ordinary American citizens into criminals by virtue of outlawing the consumption of alcohol. Prohibition also created a new criminal class that was inextricably involved in the manufacture and distribution of this formerly legal substance. By the time Prohibition was repealed, an informed observer might suggest that the United States had learned its lesson the hard way and would not make the same mistake again. Alas, the same thing is taking place in America today, wherein tens of millions of ordinary citizens are deemed criminals because they enjoy smoking marijuana (herbal cannabis), and many are imprisoned as a result. This paper analyzes relevant peer-reviewed and scholarly literature to identify the controlling factors involved in the current legislation against marijuana, and what some states and other countries have done in recent years in an effort to decriminalize its use. A summary of the research and important findings are presented in the conclusion.

Marijuana Legalization Term Paper Review and Discussion

The controversy concerning the use and value of marijuana in the United States is certainly not new, but actually dates to the middle of the 19th century; while there was not a consensus then, just as today, there were some potential benefits of the drug listed the United States Pharmacopeia until 1941.[1] The use and distribution of marijuana for whatever purpose was not officially regulated by the U.S. federal government, though, until the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 was enacted; in essence, this tax represented a legal restriction on the recreational use of marijuana because users were compelled to pay a relatively hefty sum of $100 an ounce, a charge that represented far more than the cost of the actual drug.[2] This legislation represented a death knell for the medical use of the drug even though many observers did not recognize this at the time. According to Kreit, “On its face, the Act was much more accepting of medical use of marijuana and taxed registered medical marijuana transactions at only one dollar an ounce. Nevertheless, the law made medical use of cannabis difficult because of the extensive paperwork required of doctors who wanted to use it.”[3] During the pendency of the Act when legislators were considering different points of view, the American Medical Association representative weighed on the subject “because he believed that its ultimate effect would be to strangle any medical use of marihuana,” and not surprisingly, after the Act was passed, “medical distribution of the drug had all but disappeared.”[4]

The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 may have all but stopped the legal distribution and use of marijuana in the United States, but it did little in reality to eliminate its recreational use by legions of otherwise-law abiding American citizens. Nevertheless, things became even more legalistic when the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) was enacted in 1970. In this regard, Kreit reports that, “The CSA was passed in large part because President Nixon saw regulation of the drug trade as an opportunity for the federal government to satisfy public demand to get tough on crime.”[5] Therein is the crux of the ongoing issue, then, because something is not a crime unless the government makes it one.

Based on his campaign promises to “get tough on crime” and mired in a social upheaval over Vietnam, the president was compelled to introduce a federal role in the regulation of drugs in the United States. This role was justified, at least from the federal perspective, because of the constitutional Commerce Clause and marijuana was clearly being transported across state lines, thereby provided an inroads for the U.S. government to become officially involved in its prosecution. According to Kreit, “It was in this context that marijuana was placed in Schedule I, (50) the CSA category of drugs with a high potential for abuse and no currently accepted medical use.”[6]

As a result, like the flying cars promised by scientists in the mid-20th century, the legalization of marijuana remains little more than a pipe dream, if the phrase can be excused, in most states in America today. The social movement that took place during the 1960s and 1970s in the United States and around the world appeared to represent a changing of the guard, with the old-fashioned ideas from the past being discarded in favor of more enlightened views concerning human morality and the place of the government in regulating it. In fact, most European countries have adopted a much more relaxed and enlightened view of the recreational use of marijuana today, and although it remains officially illegal in most European countries, there is little enforcement of the laws that are on the books except for a few arrests a year in order to placate the United States government because of ongoing negotiations over trade.[7] According to Steves, “Compared to the United States, many European countries have a liberal attitude toward marijuana users. They believe if ‘harm reduction’ is the aim of a nation’s drug policy, it makes more sense to treat marijuana as a health problem and regulate it like alcohol than as a criminal one.”[8]

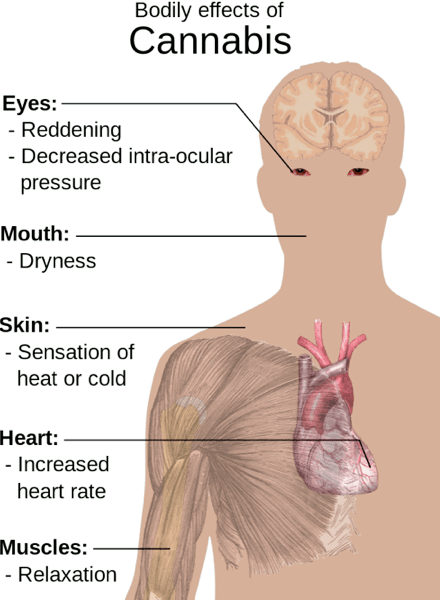

Despite a growing body of evidence suggesting that marijuana has a number of useful health-related beneficial applications such as for glaucoma and its use remains popular among tens of millions of Americans today, it would just seem logical that laws concerning its use would reflect these findings and trends. Unfortunately for pot smokers, though, keeping marijuana illegal is good business for the legal profession and prison industry, and until these motivating factors are changed, it is unclear whether any substantive changes in the laws concerning simple marijuana use and possession will remain criminal in scope.

Furthermore, like the “good old days of Prohibition,” the criminal element in American society is being enriched by keeping marijuana illegal. For example, a recent nationwide survey estimated that gang members conduct 33% of all crack cocaine sales, 32% of all marijuana sales, 16% of all powder cocaine sales, 12% of all methamphetamine sales, and 99% of all heroin sales.[9] Today, the United States locks up more of its citizens than any other industrialized country in the world and with the economy circling the drain now, the powers-that-be have good reason to keep the status quo in place. Based on U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics data, there were 37,500 federal, state and local inmates incarcerated for marijuana violations in 1998, 15,400 of them for simply possession charges only; using an average cost of $20,000 each, the government spent $750 million to imprison these offenders that could have been well applied elsewhere.[10]

This is not to say, though, that things are not changing, because they are – but slowly, and in some cases it seems that for every step forward the country as a whole takes two steps back from a legal perspective. For instance, According to Kreit (2003), “Tensions between states and the federal government over medical marijuana are not limited to California. Since 1906, nine states have legalized marijuana for medical use, a figure which is likely to increase in the coming years given the overwhelming support for medical marijuana among voters and drug policy reform leaders’ continuing focus on state ballot initiatives.”[11] In spite of these trends, no politician wants to appear “soft” on the war on drugs and such legal initiatives will undoubtedly continue to experience problems in being passed at local levels. In this regard, Murdock and Feder add that, “The systemic problems in changing drug laws through legislatures, particularly at the federal level, make further local and state initiative efforts even more probable.”[12] Nevertheless, some indications that things are changing in substantive ways include the 2002 elections, wherein voters in San Francisco approved a measure that instructed city officials to “study growing and dispensing marijuana for medical purposes in response to federal crackdowns.”[13] Likewise, in 2000, the Maine state legislature briefly debated the wisdom of launching a program that would have distributed marijuana that had been confiscated by state officials during the course of regular drug arrests to medial patients who might benefit from its use. As Goldberg reports, “One of the principle supporters of the idea, Cumberland County Sheriff Mark N. Dion, asked, ‘Shall we as a sovereign state be held hostage by the federal government simply because we intend to treat our sick and afflicted?”[14] A comparable measure was also included in a 2002 Arizona ballot initiative that, although defeated, featured a number of other drug policy reforms including the decriminalization of marijuana for simple recreational use.[15] It is to say, though, that legalizing marijuana is not only the right thing to do for these moral and healthcare reasons, but – and perhaps more importantly – it is also just good business. If the federal government legalized and regulated the sale of marijuana, the quality of the product would improve, enormous tax revenues could be generated and a cure for cancer found in a year. Furthermore, a growing number of Americans are solidly behind fundamental changes in the nation’s laws concerning marijuana. For example, according to Lynch, voters in Arizona, California, Oregon, Washington, Nevada, Alaska, and Maine have rejected the lobbying efforts of federal officials and approved initiatives calling for the legalization of marijuana for medicinal purposes[16] (2001, 37). According to Lynch, “Two sitting governors, Jesse Ventura of Minnesota and Gary Johnson of New Mexico, have declared the drug war a failure. As public opinion continues to turn against the war, we can expect more elected officials to speak out.”[17]

This is not to say, though, that things are not changing, because they are – but slowly, and in some cases it seems that for every step forward the country as a whole takes two steps back from a legal perspective. For instance, According to Kreit (2003), “Tensions between states and the federal government over medical marijuana are not limited to California. Since 1906, nine states have legalized marijuana for medical use, a figure which is likely to increase in the coming years given the overwhelming support for medical marijuana among voters and drug policy reform leaders’ continuing focus on state ballot initiatives.”[11] In spite of these trends, no politician wants to appear “soft” on the war on drugs and such legal initiatives will undoubtedly continue to experience problems in being passed at local levels. In this regard, Murdock and Feder add that, “The systemic problems in changing drug laws through legislatures, particularly at the federal level, make further local and state initiative efforts even more probable.”[12] Nevertheless, some indications that things are changing in substantive ways include the 2002 elections, wherein voters in San Francisco approved a measure that instructed city officials to “study growing and dispensing marijuana for medical purposes in response to federal crackdowns.”[13] Likewise, in 2000, the Maine state legislature briefly debated the wisdom of launching a program that would have distributed marijuana that had been confiscated by state officials during the course of regular drug arrests to medial patients who might benefit from its use. As Goldberg reports, “One of the principle supporters of the idea, Cumberland County Sheriff Mark N. Dion, asked, ‘Shall we as a sovereign state be held hostage by the federal government simply because we intend to treat our sick and afflicted?”[14] A comparable measure was also included in a 2002 Arizona ballot initiative that, although defeated, featured a number of other drug policy reforms including the decriminalization of marijuana for simple recreational use.[15] It is to say, though, that legalizing marijuana is not only the right thing to do for these moral and healthcare reasons, but – and perhaps more importantly – it is also just good business. If the federal government legalized and regulated the sale of marijuana, the quality of the product would improve, enormous tax revenues could be generated and a cure for cancer found in a year. Furthermore, a growing number of Americans are solidly behind fundamental changes in the nation’s laws concerning marijuana. For example, according to Lynch, voters in Arizona, California, Oregon, Washington, Nevada, Alaska, and Maine have rejected the lobbying efforts of federal officials and approved initiatives calling for the legalization of marijuana for medicinal purposes[16] (2001, 37). According to Lynch, “Two sitting governors, Jesse Ventura of Minnesota and Gary Johnson of New Mexico, have declared the drug war a failure. As public opinion continues to turn against the war, we can expect more elected officials to speak out.”[17]

Likewise, some members of the District of Columbia government have been advocating the legalization of marijuana. For instance, a series of reports in the Washington Times showed that, “Metro and the D.C. Department of Transportation began the pro-marijuana advertisements in 2003, displaying them on buses and bus shelters with plans for placing posters in subway stations later.”[18] (Scrap the Pot and Sex Ads, 2003, 13). According to a more recent report from McElhatton (2005) in the Washington Times’ series, despite efforts by the district’s bus company to refuse these advertisements, their display has been at least tacitly approved by the federal government. In this regard, McElhatton reports that, “Metro officials must accept advertising that promotes the legalization of marijuana now that the Justice Department has opted not to defend the transit agency’s ban on such ads.”[19] Department of Justice officials were provided with a sufficient amount of time in order to respond to these advertisements in the event the department felt compelled to appeal a federal court decision that struck down a law recently passed in Congress that stated that District of Columbia transit agencies would be in jeopardy of forfeiting federal funds in the event they accepted the advertisement promoting the legalization or medical use of such illicit drugs.[20]

As of the writing of the most recent report, the Metro had not received any further pro-marijuana ads following the Justice Department’s decision; however, a representative of the bus company advised the agency would not reject such ads unless they “showcased profanity. The transit agency is not in the business of picking and choosing what can and cannot go up,” Metro spokesman Steven Taubenkibel indicated.[21] In reality, though, absent from the above recent commentary on trends in the country is the fact that federal authorities appear to either not care or simply fail to appreciate the extent of public dissatisfaction with existing laws against simple marijuana use, possession and even cultivation for personal use, an initiative that was attempted in Alaska a few years ago.

Indeed, it would seem that fewer and fewer people across the country are abiding by the marijuana laws in their own communities, and most people are failing to take the government’s rhetoric seriously. According to Murdock and Feder, “Marijuana legalization is a conservative idea whose time indeed has come. American conservatism rests upon several key tenets. Among them: a limited government restrained by the U.S. Constitution, federalism, property rights and respect for the family.”[22] Current legislation that keeps marijuana on the criminal side of the law books, though, is directly opposed to these fundamental American principles and is based on some antiquated thinking and rationale. In this regard, Murdock and Feder emphasize that, “In fact, government’s anti-reefer madness has fueled a wholesale expansion in state activity that only marijuana’s legalization can reverse. This war is a legacy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The 1937 Marihuana Tax Act federally prohibited pot.”[23]

Reminiscent of the enormous bail-out being touted as a save-all of the nation’s struggling financial institutions, the war against marijuana continues to plod along in an apparently unstoppable juggernaut fashion no matter how many people are harmed in the process and what the social costs might be. As Murdock and Feder emphasize, “In typical New Deal fashion, government’s anti-cannabis crusade grows incessantly in cost, size and scope.”[24] Indeed, this legacy of the New Deal has had some profound consequences on the lives of millions of otherwise-law-abiding Americans over the years. In fact, according to the FBI, 401,982 Americans were arrested nationwide for marijuana offenses in 1980. By 1999, a record 704,812 were nabbed, 88% of them for possession rather than trafficking. Since cannabis arrests account for almost half (44%) of all drug apprehensions, the Marijuana Policy Project (MPP) estimates that the government’s war on recreational marijuana users costs American taxpayers a staggering $9.2 billion each year (emphasis added).[25]

Certainly, there are some valid arguments against the legalization of marijuana that should be taken into account in this analysis, just as there are some profound arguments in support of it. Some of the pro and con arguments for the legalization of marijuana include the following:

Table 1: Representative Pros and Cons of Legalizing Marijuana

Table 1. Representative pros and cons of marijuana legalization in the United States today.

Marijuana Legalization Term Paper Conclusion

When Prohibition was repealed in December 5, 1933, the entire country was both relieved that the government’s failed experiment in legislating morality was over, and elated that they could once again indulge in a pastime that many people enjoy without being labeled a criminal in the process. In a similar fashion, it is reasonable to conclude that when the day comes that marijuana is legalized across the country for medical or personal or whatever type of use, tens of millions of Americans – indeed, perhaps a majority of its citizens – will no longer be characterized as criminals because of their possession and use of a simple vegetable substance with some mild psychoactive properties that should not be the focus of governmental regulation in the first place. Other countries with relaxed or decriminalized laws concerning marijuana have not experienced the social breakdown predicted by the gloom-and-doom naysayers, and it appears that the only ones benefiting from keeping pot illegal are members of the criminal justice system and the legal profession.

Legalization of Marijuana Term Paper Bibliography

Cameron, Kenzie A., Shelly Campo, and Dominique Brossard. “Advocating for Controversial Issues: The Effect of Activism on Compliance-Gaining Strategy Likelihood of Use.” Communication Studies 54 (2003): 265.

Goldberg, Carey. “Maine Sees Medical Use for Its Seized Marijuana.” New York Times (March 14, 2000): A16.

Kreit, Alex. “The Future of Medical Marijuana: Should the States Grow Their Own?” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 151 (2003): 1787.

Lynch, Timothy. “War No More: The Folly and Futility of Drug Prohibition.” National Review 53 no. 2 (February 5, 2001): 37.

McElhatton, J. “Metro Must Accept Pro-Marijuana Ads.” The Washington Times (January 28, 2005): B02.

Murdock, Deroy, and Don Feder. “Symposium.” Insight on the News 17 no. 37 (October 1, 2001): 40.

Rosenthal, Lawrence. “Gang Loitering and Race.” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 91 no. 1 (2000): 99.

“Scrap the Pot and Sex Ads.” The Washington Times (October 4, 2003): A13.

Steves, Rick. Rick Steve’s Europe through the Back Door. New York: Avalon Travel, 2009.

Footnotes (re: Marijuana Legalization Term Paper)

- Alex Kreit, “The Future of Medical Marijuana: Should the States Grow Their Own?” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 151 (2003), 1787. ↑

- Kreit, 1787. ↑

- Kreit, 1787. ↑

- Quoted in Kreit at 1787. ↑

- Kreit 1787. ↑

- Kreit 1787. ↑

- Rick Steves, Rick Steve’s Europe through the Back Door (New York: Avalon Travel, 2009), 494. ↑

- Steves, 494. ↑

- Lawrence Rosenthal, “Gang Loitering and Race.” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 91 (2000), 99. ↑

- Deroy Murdock and Don Feder, “Symposium.” Insight on the News 17 no. 37 (October 1, 2001), 40. ↑

- Kreit, 1788. ↑

- Kreit, 1788. ↑

- Quoted in Kreit at 1788. ↑

- Quoted in Carey Goldberg, “Maine Sees Medical Use for Its Seized Marijuana.” New York Times (March 14, 2000) at A16. ↑

- Kreit, 1788. ↑

- Timothy Lynch, “War No More: The Folly and Futility of Drug Prohibition.” National Review 53 no. 2 (February 5, 2001), 37. ↑

- Lynch, 37. ↑

- “Scrap the Pot and Sex Ads.” The Washington Times (October 4, 2003), A13. ↑

- J. McElhatton. “Metro Must Accept Pro-Marijuana Ads.” The Washington Times (January 28, 2005), B02. ↑

- McElhatton, B02. ↑

- Quoted in McElhatton at B02. ↑

- Murdock and Feder, 40. ↑

- Murdock and Feder, 40. ↑

- Murdock and Feder, 40. ↑

- Murdock and Feder, 40. ↑

Bibliography Tool: How to Reference This Paper in Different Citation Styles

If you don't see the paper you need, we can write it for you!

Established in 1995

900,000 Orders Completed

100% Guaranteed Work

300 Words Per Page

Simple Ordering Process

100% Private and Secure

We can write a new, 100% unique paper!

Search Papers - Wed, Apr 24, 2024

Navigation

Home | Order | FAQ

Samples | Contact Us

Share With Friends